For years now, I’ve offhandedly mentioned evangelicals’ enduring hatred of postmodernism. They don’t understand what it is, but they sure know they hate it! Today, let’s plunge into what it is, why they hate it so much, and why they can’t ever truly get away from it.

(This post and its audio ‘cast first went live on Patreon on 10/21/2025. They’re both available now! From introduction: Trifle recipe.)

SITUATION REPORT: OMG, everyone! It’s POSTMODERNISM!

On October 11, Christian Post ran a plaintive opinion post that attacked postmodern churches. The title of this charming throwback to the 2010s’ Keyboard Wars is: “7 signs you’re in a postmodern church.”

OH NOES! Not that! Anything but a postmodern church!

As you might guess, it’s a standard-issue listicle of the sort evangelicals adored back in the 2010s. Here are the 7 signs, quoted and presented without comment (yet; don’t worry, we’re getting there):

- They don’t preach the absolutes of salvation.

- They have low standards of morality for volunteers and musicians.

- Sermons are self-help messages without any reference to sin and repentance.

- Their view of societal ethics is relativistic.

- Anyone can be a member without proper vetting regarding doctrine or salvific status.

- The focus is more on a worship experience than on theological depth in preaching.

- Their main goal is to garner crowds — not to make disciples.

Incidentally, QuillBot (an AI detector) thinks 86% of the OP (original post) is AI-generated. Grok was more generous, thinking instead that the writer, Joseph Mattera, or editorial staff somewhere used AI to polish the work. Grok was quite certain of that point, too, incidentally, pegging 60-70% of the text being AI-assisted. The truth likely rests in the middle somewhere between those poles.

Normally, I wouldn’t say anything about AI. But as I hope you’ll see by the end of today’s topic, I’m not sure anything could possibly scream postmodernism quite as loudly as an evangelical using AI for a post complaining about postmodernism.

IN THE WILD: Evangelicals’ postmodernism complaints

Out in the wild, evangelicals have a strangely consistent misunderstanding of postmodernism. From Word on the Streets, an evangelistic site:

A postmodern world view states that there is no objective, absolute truth; that ”truth” is what you believe it to be. Something can be “true for you, but not true for me”.

Via Emmaus insists that postmodernism infests only weaker “false philosophies,” like “liberal theologies.” Whew! But don’t relax yet, evangelicals:

In contrast to liberal theologies, Evangelicalism’s commitment to the Scriptures as authoritative serves as a defense mechanism against false philosophies. However, the fact that many evangelical theologians have appropriated deleterious methods from postmodernism indicates that somewhere there is a weakness.

Some evangelicals use the term “relativism” to describe postmodernism, like we see at the site Study with Friends:

Relativism is a philosophical belief that there is no absolute truth. It stands in stark contrast to the Christian belief system which holds to objective and absolute biblical truths, one of which is that Jesus is the only way to salvation.

In 2001, the Evangelical Lutheran Synod’s site published an authoritative essay describing postmodernism:

Unlike philosophies that have preceded it, it [postmodernism] does not claim to offer a worldview, that is, a basic set of truths that tie all of life together in some meaningful way… because the basic concept behind postmodernism is that there are no absolute truths, no sure and certain foundations upon which our knowledge and beliefs can stand.

Then, we have a 2025 essay from evangelical high schoolers in Kennesaw, Georgia. In it, they lament the “watering down” of TRUE CHRISTIANITY™. Of the links, one goes to the hardliner Calvinist site The Gospel Coalition, so you know it’ll be a fun read. Here’s what these students wrote:

Instead of distorting Scripture in the views of social extremism, current ideologies that aim to reflect the progressive adjustment in ideals, such as Postmodernism, have instead watered down Christianity in an attempt to fix past issues.

As for The Gospel Coalition itself, here’s the 2018 post they wrote that so impressed those Georgia high schoolers:

Postmodernism attacks universal truth claims and challenges the idea that we might find a sure foundation for truth. But this rejection hasn’t stopped postmodernism being dogmatic—far from it. For late postmodernism, truth isn’t something to argue about, it’s something you fight for! Cue, deplatforming campaigns; campus riots and ominous challenges to the notion of free speech. This way lies the mob, The Reign of Terror and the Cultural Revolution.

But we do have a foundation. [Spoiler: It’s totally Jesus! Bet you didn’t see that coming!]

Also in 2018, Answers in Genesis ran an essay that links the postmodern philosophy movement to postmodern art and architecture. (The essay’s writer isn’t a fan of either.) But its conclusion doesn’t care about art:

Since the postmodernist thinks there is no real valid way to measure truth from error, acceptable from unacceptable, or right from wrong, all beliefs and perspectives are determined to be equally valid. [. . .] Postmodernism embraces relativism to the highest degree. Relativism is the idea that truth and moral values are not absolute but are relative to the persons or groups holding them.

The sheer sameness in these sources tells us something very important about this moral panic over postmodernism. In a minute, I’ll show you what that important thing is.

The common threads in evangelical sources

First, let’s explore the common threads in evangelical thinking about postmodernism.

Many sources accurately describe the predecessor of postmodernism. Unsurprisingly, it’s modernism. Though not all sources agree on the source of modernism itself, many suggest it began with the Enlightenment. During the Enlightenment period, commonly reckoned as 1685-1815, Europeans underwent a massive reorientation in their thinking. They challenged religious authorities and dogma. They began approaching truth-seeking with more reality-based methods—namely the scientific method.

So evangelicals understand that postmodernism is a reaction to modernism.

But from there, everything falls apart.

In evangelical minds, postmodernism becomes a free-for-all. It creates a world with absolutely no way to ascertain what’s true or false. In that world, Christianity occupies the same level playing field as every other set of claims. Nothing elevates them above anybody else. So nobody has a reason to treat Christians’ claims as more authoritative than anybody else’s.

Evangelical sources are also quite certain that Hitler’s rise to power, China’s Cultural Revolution, and a host of other ills would never have happened in a premodern world. Somehow, they never mention the Inquisition, which began well before the Enlightenment. (In fact, European governments began abolishing it during the Enlightenment period.) Interestingly, though, postmodernism hinges on scientific advances like computers, which are decades later than anything named as a postmodern evil.

(Hang in there. We’re getting to the history of postmodernism in just a moment.)

Finally, something High and Low Christians can both embrace!

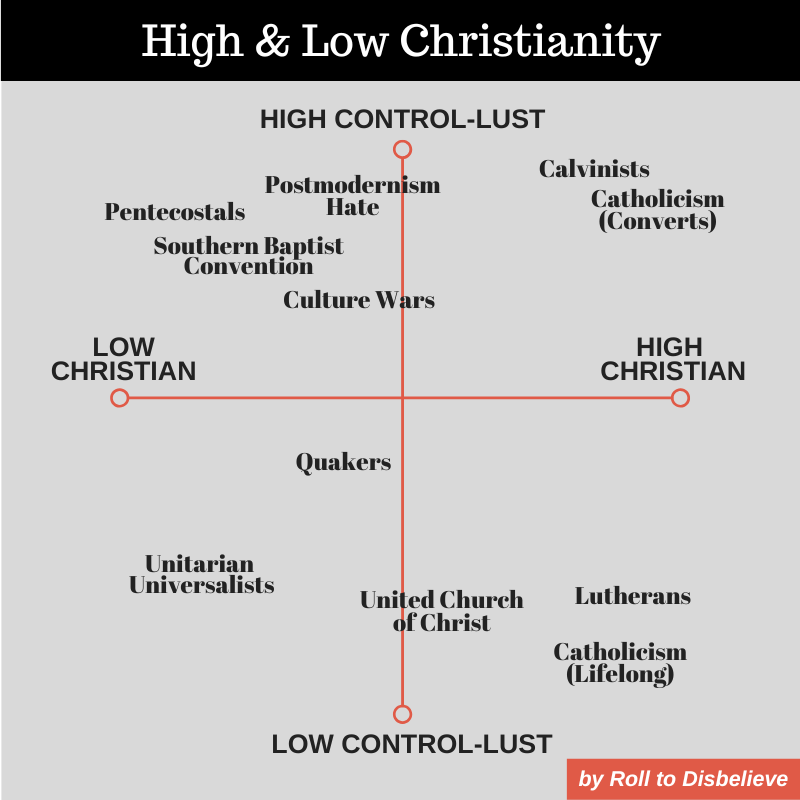

(Terminology: High Christianity = more scholarly, considers itself intellectual, more ritual-oriented; Low Christianity = orgiastic, emotion-driven, thoroughly anti-intellectual, more folk-religion devotions and superstitions, more spontaneous.)

As you might have guessed, postmodernist hate is a high control-lust trait. Interestingly, though, it’s found in both Low and High Christian groups. So it lives way on the upper middle of our High/Low Christianity graph, which I’ve updated:

Now, let me show you that important thing I mentioned earlier about the sheer sameness of evangelicals’ wackadoodle response to postmodernism:

Like other high control-lust facets of evangelicalism, this one’s largely artificially engineered.

I myself was a fundamentalist (Pentecostal) in the 1980s and early 1990s, and I do not remember a single evangelical or fundamentalist at the time complaining about postmodernism. And my circle was largely college-based for most of that time, so if anyone would have noticed, we would have. No, none of us noticed anything amiss about our studies or universities.

Rather, a few influential evangelicals pushed the idea hard just as the tribe began fusing in earnest with fundamentalists. It caught on with both sides of the aisle. It felt similar enough to the rest of the culture wars to catch on with fundamentalists. Importantly, however, it was highbrow enough to sound intellectual to the increasingly anti-intellectual evangelical post-fusion crowd.

The secret supervillain origin story of evangelicals’ war on postmodernism

Here’s how postmodernism became an evangelical boogeyman and snarl world:

Intellectuals began noticing postmodernism in the 1970s. In 1979, Jean-François Lyotard published The Postmodern Condition. It wasn’t a particularly good book, but it got philosophers thinking about how technology affected how humans acquire and use knowledge. Then, in 1990, Thomas Oden published After Modernity…What?

At the time, he couldn’t have chosen a better title, nor a better enemy to attack than “modernity.” In 1990, the modern world completely spooked evangelicals. At the time, most influential evangelical leaders were Boomers. Computers had begun making major cultural inroads with Gen X. Feminism was gaining ground. The Satanic Panic had largely failed to get them back their lost cultural power. The first cracks in Christianity’s dominance in America began showing. And worst of all, normies began challenging apologists’ soft-shoe huckster routines and ducking out of church services. So yes, evangelicals had very little love for anything modern.

Back then, I’m sure evangelicals had noticed fundamentalists’ affection for what they called “old-time religion.” Both groups yearned to practice “original first-century Christianity.” Even I, as a Pentecostal, shared that yearning. (Unsurprisingly, the fusion hinged on evangelicals accepting the primary tenet of fundamentalism: biblical literalism and inerrancy.) Who better to merge with?

Throughout the 1990s, various evangelicals wrote books criticizing postmodernism: Roger Lundin (The Culture of Interpretation, 1993), Gene Edward Veith (Postmodern Times, 1994), and Stanley Grenz (A Primer on Postmodernism, 1996). They also include David Dockery, who became a Southern Baptist-branded seminary leader. He edited The Challenges of Postmodernism in 1995. Meanwhile, David Wells attacked postmodernism twice—in 1993 (No Place for Truth) and 2005 (Above All Earthly Pow’rs); he also wrote sermons on websites attacking it.

By 1998-1999, as articles from Ministry and Christianity Today show, postmodern was a culturally-understood shorthand for everything post-fusion evangelicals hated. As one more-sensible Calvinist reveals, ultraconservative Calvinist seminaries even began assigning students postmodern books to read in the 90s—so they could hate it more!

Toward the end of the 1990s, the fusion of evangelicals with fundamentalists largely finished. At last, everything the new tribe didn’t like was postmodern. Yes. It was so simple. Everything that detracted from their power was postmodern. Postmodernism caused all the other ills they saw in modern culture. Definitely, it had caused their decline.

It had become their worst enemy.

What postmodernism actually is

After all this brouhaha, now let’s briefly talk about what postmodernism actually is. As mentioned, it is indeed a response to modernism. At its core, modernism expresses faith in humans’ ability to figure out what’s true and false through exploring reality itself. It expresses optimism in our ability to use those reveals to improve our world. In simple terms, science = learning about reality = human progress = world improvement. It places reality itself at the forefront, considering scientific truths as universal.

By contrast, postmodernism expresses distrust in our ability to accurately discern those reveals at all. It also understands that when we communicate what we think is reality to someone else, we’re of necessity layering it into narrative-driven language, which is intrinsically subjective. Postmodernism is not as certain as modernism in our ability to accurately interpret our experiments’ results, much less to use them to improve the world. It thinks the truth’s way more complicated and complex than modernists can imagine. And what one culture considers universal truth, another might not recognize at all.

Importantly, postmodernism doesn’t say there are no objective truths. It just has major questions about identifying one and communicating it to others.

So in postmodernism, when people encounter reality, they don’t understand it as it is, but rather as our language describes it. The ideas we express aren’t about their subject at all, but rather about the “signs” that we create about them with language. Those signs change over time, and in relation to the changes in other signs of language. They also change with a culture’s existing power structures. (If you’ve heard the saying “history is written by the winners,” that’s how.)

What’s really happening here with the postmodernism squabble

Evangelicals have always had a tough time differentiating between reality-truth and religious-truth.

Reality-truth is stuff in the real world: Stars, planets, biology, dates and times, even—sigh, I grudgingly admit—the state of Wyoming. By contrast, religious-truth is what believers must have faith to believe exists because it utterly lacks reality-truth: souls, an afterlife, gods, demons and angels, and miracles.

Reality-truth can and must be tested and supported with modernist practices like the scientific method. Religious-truth can’t, though, and never could. Only through the religious power structures of premodernism could Christian leaders even try to make a claim to having a stranglehold on universal, authoritative reality-truth.

Evangelicals like to imagine that their religious-truth is, in fact, reality-truth.

See, today’s evangelicals value reality-truth. And they don’t want to believe in anything that can’t withstand reality-based methods of fact-finding and claim-supporting. They try to smash and warp reality-truth into their beliefs, all to make their religious-truth feel more like reality-truth.

That’s why they buy into Creationism. Creationism pretends to find real-world PROOF YES PROOF of the Bible’s myths. Modernism can easily tell that those myths didn’t really happen, which calls the entire authority of the Bible into question for literalist-inerrantists—like evangelicals!

When evangelicals rail against ickie evil postmodernism, what they’re really complaining about is the way that people automatically consider religious-truth subjective rather than objective. Christians depend mightily on the borrowed authority they get from claims to having a religious-truth that is also reality-truth. Without that authority, they can’t make sales.

So when a prospect tells them Christianity doesn’t work for them, they know what that really means. The prospect is really saying they’re willing to consider Christian claims only from a subjective religious-truth standpoint that places Christianity on the same level as other religions/philosophies.

Unfortunately, Christianity simply cannot compete that way. It never could. That’s why there was an Inquisition in the first place. It’s also why the first task of evangelists tends to be persuading the prospects that Christianity is the only valid source of reality-truth. That first task tends to be almost impossible in non-Christian countries.

Why evangelicals shouldn’t hate postmodernism at all

But aw, c’mon, fellas, there’s no need to fight. Really, we’re all a little postmodern here. And that definitely includes evangelicals, whether they like it or not. They can’t really help it, any more than the rest of us can. It’s just how our culture works nowadays. It’s in the very air we breathe.

The very postmodern structures that elevate subjective experiences and reality helped evangelicals fuse with fundamentalism to begin with. From personal experience, I can tell you that fundamentalists always placed a high value on divine revelation, orgiastic emotional catharsis, prophecy, and divine portents. They always knew that Yahweh could and often did change course based on what his followers prayed for him to do. It’s why they prayed by the tens of thousands for one pastor who got struck down young by cancer: Yahweh might have slated him to die of it, but enough prayer could change everything. (Spoiler: It didn’t.)

Pentecostals also knew from long experience that Yahweh often moved his glory from one practice or group to another. The entire early-20th-century Azusa Street Revival, revered by Pentecostals, was about Yahweh pouring out his Holy Spirit on Christians to bring them back to 1st-century practices like speaking in tongues! So what one group of Christians considered Yahweh’s will for humanity could and frequently did change as Yahweh saw fit.

Even postmodernism’s deconstruction of beauty and form can be detected in modern evangelicalism. They at least pay lip service to Jesus’ constant inversion of societal standards and ideals: He ate with tax collectors, magically healed leprosy, and declared that the “first” in society would be “last” in Heaven, while the lowliest would rule. He railed against authority figures, particularly religious ones, and commanded his followers to selflessly help the lowest-status people in their society.

Evangelicals don’t really want to do any of that. But it’s part of their mythology about themselves anyway, despite reality saying the opposite—which, itself, sure sounds suspiciously postmodern.

The most popular Low Christian evangelical practices couldn’t exist without a postmodernist take on Christianity itself

Every so often, we can see evangelicals grappling with this painful reality about postmodernism. It’s their enemy, but also their friend. It’s a hated boogeyman, but also their most salacious lover.

Postmodernism leads evangelicals to love conspiracy theories that are completely divorced from reality. Their Dear Leaders have stripped from their followers any reliable way to discern reality-truth in claims, and they deeply distrust any secular-seeming method of gauging claims—because those very methods always find their claims wanting. So it’s easy for hucksters to sell the flocks fake news by simply building upon the objectively-false beliefs the flocks already hold.

I could go on, but the point remains the same. Modern evangelicalism really couldn’t exist without postmodernism. This fact dismays some Christians, like Anna Rollins, who wrote this for Christian Century in August 2025:

The same demographic that, 20 years ago, was adamant about truth—White evangelicals—now largely embraces what they once would have derided as relativism. Like so many other millennial evangelicals who grew up on a steady diet of anti-postmodernism, I continue to feel astounded by this moral hypocrisy.

She’s not wrong. Others, however, emerge from studying postmodernism with a far more nuanced understanding of both the philosophy and its effects on evangelicalism as a whole. For theology professor Dale Coulter, that study led him into “a deeper appreciation of my Pentecostal heritage.” He’s dismayed at how so many evangelical leaders oversimplify and vilify postmodernism.

Nobody’s more relativistic and postmodern than evangelicals

So now, let’s turn to those “7 signs you’re in a postmodern church,” our OP of the day (relink). Let’s examine them from the lens of actual postmodernism and the real beef going on here between competing interpretations of Christianity:

1. They don’t preach the absolutes of salvation.

I’d really like some names here. I know of no Christian churches that teach anything different from Jesus being “the way, the truth, and the life.”

2. They have low standards of morality for volunteers and musicians.

Hilariously, he thinks “in historic Christianity, those who minister [. . .] were held to high biblical standards.” WHEN? WHERE? That’s never been true. But wait, there’s more! In postmodern churches, “pragmatism trumps purity.” So obviously, that’s where you find the worst hypocrites. Oh, bless his cotton socks. Does he really not realize that the churches he likes best are filled with predators in ministry?

3. Sermons are self-help messages without any reference to sin and repentance.

Again, I’d like names. “True preaching,” as he calls it, “must confront sin, point to the cross, and call people to repentance (Acts 2:38).” But this true preaching doesn’t seem to do a single thing to improve the actual behavior of hypocritical evangelicals.

(Also, a pastor who does too much “true preaching” will find himself out of a job. The entire central conflict in This Present Darkness involved one such pastor.)

4. Their view of societal ethics is relativistic.

Societal ethics is one of the most relativistic things there is, and you’d think a Christian would be more aware of that. He name-checks “God’s design for marriage” as being between a man and woman, when it’s really more like the 2010s diagram we all loved back then: One man plus all the wives and sex slaves he could afford.

5. Anyone can be a member without proper vetting regarding doctrine or salvific status.

OMG, he can’t control how other churches incorporate newcomers to their groups? OH NOES! Also, he’s hinting at member covenants here, which are a bright red flag.

6. The focus is more on a worship experience than on theological depth in preaching.

He’s very upset about services that feel more like “entertainment rather than adoration.” But people don’t join churches to learn deep-dive theology. They join to worship and spend time together, and maybe learn a bit as long as it doesn’t demand too much of them.

7. Their main goal is to garner crowds—not to make disciples.

Ah, another red flag here: “discipling,” which is evangelical Christianese for an intense form of direct control. But beyond that, of course evangelical pastors care about membership numbers. Their entire paycheck depends upon it.

In summary, this guy’s just throwing a tantrum because his preferred flavor of Jesusing doesn’t dictate the choices of every other church in America.

Unfortunately, unless he can convince all other Christian leaders that his authority trumps theirs, that his viewpoint should be given primacy, that his opinions carry more weight than their own, other pastors will continue to ignore him and his shrill little demands. And he will have to just die mad about it.

To me, nothing sounds more sublimely postmodern!

NEXT UP: We review various ways evangelicals have devised to convert postmodernists! It’s gonna be such a hoot, I can already tell. See you soon! <3

Please support my work!

Thanks for reading, and thanks for being part of our community! Here are some ways you can support my work:

0 Comments